How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution

We are marching towards a future in which three-quarters of humans live in cities, and a large portion of the planet's landmass is urbanized. With much of the rest covered by human-shaped farms, pasture, and plantations, where can nature still go? How are our manmade environments changing the evolution of animals and plants around us? Is evolutionary adaptation taking place at unprecedented speeds?

Carrion crows in the Japanese city of Sendai have learned to use passing traffic to crack nuts. Lizards in Puerto Rico are evolving feet that better grip surfaces like concrete. Europe’s urban blackbirds sing at a higher pitch than their rural cousins, to be heard over the din of traffic. How is this happening?

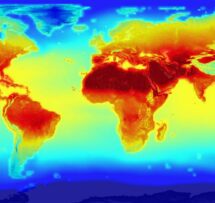

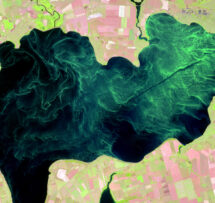

With human populations growing, we’re having an increasing impact on global ecosystems, and nowhere do these impacts overlap as much as they do in cities. The urban environment is about as extreme as it gets, and the wild animals and plants that live side-by-side with us need to adapt to a whole suite of challenging conditions. They must manage in the city’s hotter climate (the “urban heat island”); they need to be able to live either in the semi-desert of the tall, rocky, and cavernous structures we call buildings or in the pocket-like oases of city parks (which pose their own dangers, including smog and free-ranging dogs and cats); traffic causes continuous noise, a mist of fine dust particles, and barriers to movement for any animal that cannot fly or burrow; food sources are mainly human-derived.

And yet, the wildlife sharing these spaces with us is not just surviving, but evolving ways of thriving. As more and more wildlife is carving out new niches among humans, evolution takes a surprising turn. Urban animals evolve to become more tolerant, curious and resourceful, city pigeons develop “detox”-plumage, and weeds growing from cracks in the pavement adjust their seeds. Some city animals are even on their way of becoming an entirely new species. Thanks to evolutionary adaptation taking place at unprecedented speeds, plants and animals are coming up with new ways of living in the seemingly hostile environments of asphalt and steel that we humans have created. We may be on the verge of a new chapter in the history of life -- a chapter in which much old biodiversity is, sadly, disappearing, but also one in which a new and exciting set of life forms is being born.

Menno Schilthuizen is one of a growing number of “urban ecologists” studying how our manmade environments are accelerating and how this is driving evolution. He will talk about just how stunningly flexible and swift-moving natural selection can be. In his bestseller book ‘Darwin Comes to Town’ (2018) he draws on impressive examples of adaptation to share a vision of urban evolution in which humans and wildlife co-exist in a unique harmony. It reveals that evolution can happen far more rapidly than Darwin dreamed, while providing a glimmer of hope that our race toward overpopulation might not take the rest of nature down with us.

Menno Schilthuizen

How the urban jungle drives evolution

We are marching towards a future in which three-quarters of humans live in cities, and a large portion of the planet's landmass is urbanized. With much of the rest covered by human-shaped farms, pasture, and plantations, where can nature still go? How are our manmade environments changing the evolution of animals and plants around us? Is evolutionary adaptation taking place at unprecedented speeds?

Talk by

Menno Schilthuizen

Menno Schilthuizen is a Dutch evolutionary biologist / ecologist and a professor in character evolution and biodiversity at Leiden University. He is a permanent research scientist at Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden. In particular, his studies have concerned land snails and beetles. He has published numerous articles about evolution and ecology and four popular science books, including ‘His Nature's Nether Regions’, on the evolution of genitalia, and ‘Darwin Comes to Town’ on urban evolution. Besides his academic positions, Schilthuizen works as an independent science communicator via his own company, Studio Schilthuizen. Recently, together with biospeleologist Iva Njunjić, he has begun the organisation Taxon Expeditions, which organises field courses for citizen scientists to Borneo and other places, and allows non-biologists to be involved in the discovery and naming of new species.