Before we forget: Early dementia diagnosis and treatment

Before we forget: early dementia diagnosis and treatment development

How can we discriminate different dementia types in early stages, before clinical symptoms? Which molecules change in body fluids in early stages of dementia? Can we identify specific biomarkers for each dementia type? Can we use these molecules to monitor positive effects of treatments? How can we accelerate the process of biomarker development?

Not being able to recall memories, forget names from loved ones or where your house is located. Many of us may fear this to happen when we get older, and may have a grandmother or grandfather suffering from it and affecting the family and social circle around them. But what happens when you get this when you’re not even 40 years old and in the middle of life?

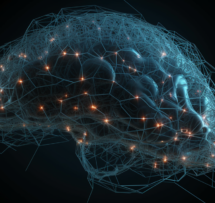

Dementia is a threatening disease due to its increasing incidence in the aging population, bulging costs and inhumane clinical course, while no cure is currently available. An estimated 40 million individuals suffer from dementia worldwide, 8.8 million in Europe, a number expected to double every 20 years. Nowadays, dementia is only diagnosed by the symptoms of cognitive decline; in other words: when a person’s basic memory functions do not work properly anymore, and they start to forget things, names and events. However, the disease starts to develop in the body years, if not decades before we can notice the first symptoms. This calls for solutions to detect such processes in our body.

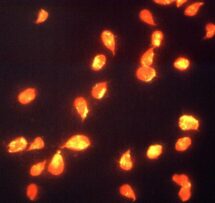

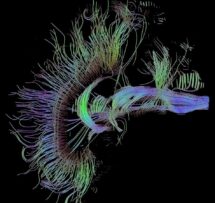

Biomarkers, or biological markers, are increasingly used in medical science to detect diseases and develop personalised treatments. Biomarkers are signs of biological processes that can be measured in a person. They indicate where and when a disease develop and what happens in a sick person’s body. Charlotte Teunissen is working on a way to use these markers to detect the earliest signs of dementia in our bodies.

To make progress in the development of effective drugs for dementia, there is thus an urgent need for biomarkers that we can use to capture dementia before clinical symptoms appear. For example, Alzheimer diagnosis is nowadays strongly supported by the analysis of the proteins amyloid and tau in bodily fluids.

Charlotte’s work is promising for precision health, that may lead to an early and specific diagnosis, as well as gaining a closer look on the development of this complicated disease. On the other hand, ethical issues arise: when there is not a cure yet, will it make sense for younger people to know they might get dementia? Or will this support the development of a cure?

Charlotte Teunissen

Before we forget: Early dementia diagnosis and treatment

Not being able to recall memories, forget names from loved ones or where your house is located. Many of us may fear this to happen when we get older, and may have a grandmother or grandfather suffering from it. But what happens when you get this when you’re not even 40 years old and in the middle of life? How can we discriminate different dementia types in early stages? Can we identify specific biomarkers for each dementia type?

Talk by

Charlotte Teunissen

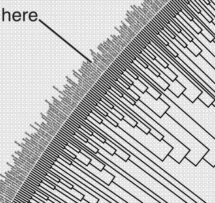

Charlotte Teunissen’s mission is to improve care of patients with neurological diseases by developing body fluid biomarkers for diagnosis, stratification, prognosis and monitoring treatment responses. She is the first female professor in Neurochemistry in Europe. Studies of her research group cover the entire spectrum of biomarker development, starting with biomarker identification, followed by biomarker assay development (a procedure in molecular biology for testing or measuring the levels of a drug or biochemical in an organism) and analytical validation, and extensive clinical validation to ultimately implement novel biomarkers in clinical practice. Charlotte has extensive expertise with assay development on state of the art technologies, such as Quanterix ultrasensitive SimOA technology, and in implementation of vitro diagnostic technologies for clinical routine lab analysis. She is responsible for the biobank of the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort. She has an impressive track record in development of guidelines for biobanking and international collaboration for biomarker studies. Recently, she received funding under the Marie Curie International Training Network to train 15 PhD students to become the next generation of effective biomarker developers for dementia. In 2018, she won the VIVA400 Knappe Koppen award for promising female scientists and innovators in the Netherlands. Finally, she has made it to the three final nominees of the Piper-Heidsieck Leading Ladies Award within the category of societal impact.